In 2018, more than 6,300 people in the U.S. were sickened via toxic mushroom ingestion, according to the most recent statistics from the National Poison Data System (NPDS). Without immediate treatment, consuming poisonous species can lead to liver damage and even death. And among mushroom-related deaths, medical experts have estimated that around 90 percent are linked to a specific category of toxins known as “amatoxins.”

Thankfully, scientists at the Department of Agriculture (USDA) have developed a simple test strip that can detect the presence of amatoxins found in wild mushrooms in a matter of minutes—a tool they hope can help foragers avoid food poisoning. The new technology—detailed in a paper published by peer-reviewed Toxins journal—can detect the common toxins in both urine and mushroom samples at concentrations as low as 10 parts per billion.

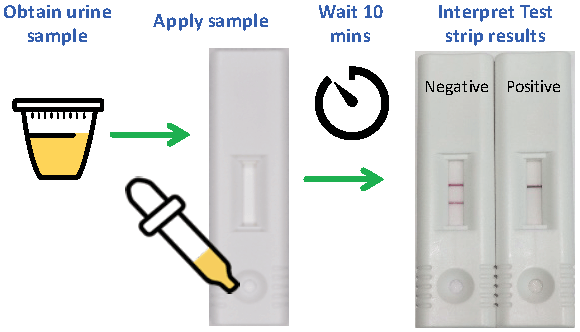

“We’re hoping that this test can help physicians and even veterinarians to quickly identify an amatoxin-specific poisoning,” says Candace Bever, microbiologist at USDA’s Foodborne Toxin Detection and Prevention Research Unit and lead scientist of the paper. “If it can be identified, then treatment can begin sooner, rather than waiting to rule out everything else.” Bever’s test presents results within 10 minutes.

Amatoxin-containing mushrooms include two ominously named species called “death caps” and “destroying angels.” Death caps are frequently mistaken for non-toxic species like the paddy straw mushroom which appears nearly identical. Some people eat foraged mushrooms because the possibility of poisoning doesn’t even cross their minds. Still others accidentally ingest amatoxin-containing varieties, mistaking them for psychedelic mushrooms (not so groovy).

“Most of the poisonings are people who just really don’t have a clue and decide that mushroom foraging is a good idea and haven’t developed the skills to do it,” says Tom Bruns, a professor of mycology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Candace Bever / Toxins

The new test harnesses a similar mechanism to the one used in the common pregnancy test, called a “lateral flow immunoassay.” A sample (urine or mushroom concentrate) is applied to one end of a cellulose strip, which then responds with a colored line depending on the presence or absence of a particular compound. Bever’s team conducted experiments on the test for accuracy by spiking 96 samples of human urine with varying levels of amatoxin. The experiment yielded a true positive rate—the proportion of amatoxin-containing samples correctly identified as such—of 92.3 percent, and a true negative rate of 100 percent. They also conducted the experiment on 38 samples of dog urine submitted by owners who suspected their pets had been poisoned. Man’s best friends are a common victim of toxic mushrooms, which they can accidentally eat when roaming outdoors.