People who excel in their chosen field sometimes hope their children will want to follow in their footsteps. That’s not always the case when it means taking on the grueling, competitive and long hours of the restaurant business.

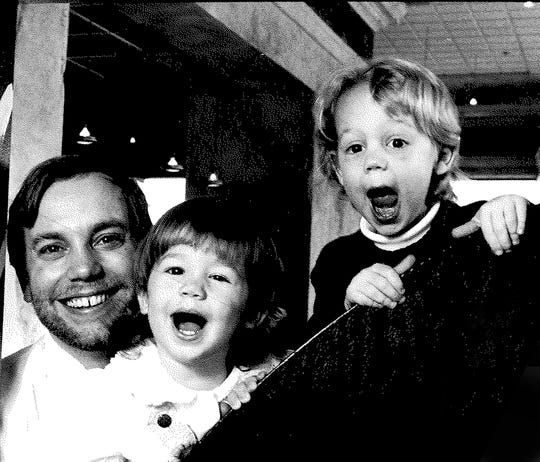

Award-winning chef Jimmy Schmidt has blazed a path for his adult children — certified sommelier Taylor and executive chef Stephen, who work at top Detroit restaurants — that started when they still had baby teeth and were working with him at his game-changing restaurant Rattlesnake Club and others in the 1990s.

The riverfront fine-dining destination, which still thrives today almost a decade after Schmidt moved on to other ventures, was given various “Best Restaurant” awards from local and national publications.

It was there that Schmidt earned the 1993 James Beard Foundation award for Best Chef Midwest. Schmidt knew Beard from Detroit’s restaurant scene of the 1980s during his tenure at the original London Chop House, where he was under the wing of owner Lester Gruber.

That was when I was an infant,” Schmidt joked as he discussed his early days at the Chop House, where he would be sent to France on wine trips for Gruber, who was friends with chefs like Beard and others who Schmidt says “built the foundation of the American food scene.”

In the 1980s, Detroit had a huge food scene in part because of the booming auto industry, he said.

“It was the three-martini lunch,” he said. “We had Dover sole flown in from the North Sea … steak and eggs and a bottle of ’61 Brane-Cantenac. It was $300 per person for lunch.”

Today, Schmidt is operating at Lucky’s Noble BBQ inside the food hall and restaurant incubator Fort Street Galley, just steps from a remodeled London Chop House.

Just blocks from Lucky’s, Schmidt’s oldest son, Stephen Schmidt, is the executive chef at cocktail-forward Standby, one of downtown Detroit’s more prominent restaurants.

His only daughter, Taylor Schmidt, recently earned her sommelier certification and is the bar manager at Michael Symon’s Roast, which at 10 years old is a stalwart of Detroit’s revived restaurant scene.

Schmidt’s three younger sons — Michael, 18, Jasse, 11 and Caden, 10 — all work with him at Lucky’s on and off as the older Schmidts did at Rattlesnake.

Restaurants are ‘a sound career’

On the surface it may be obvious that the two eldest children of a three-times James Beard Award-winning chef would get such high profile positions at notable Detroit dining destinations. It may be fair to say they had a leg up from working in Dad’s restaurant. But you don’t become a sommelier unless you have serious expertise, and you can’t lead one of the most popular kitchens in town without real talent.

“I warned them not to get into the business because it’s tough on family life,” said Schmidt, who in spite of this is clearly proud of the path his two oldest children have taken.

While they thought of the industry as “a sound career,” as Taylor puts it, both elder Schmidt kids originally sought out different creative occupations.

Stephen is a rock musician and is working on a new album with his punk band the Ill Itches. Taylor studied darkroom photography among other things at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and later got into welding and metal fabrication, all while keeping a foot in the hospitality industry.

Schmidt says both children have great palates.

“You can know how to cook and not know how to taste,” he said, regarding the importance of understanding flavors in food and drink.

Taylor and Stephen not only grew up helping make pastries and bringing bread to the tables at Rattlesnake, they’ve also seen their father run restaurants across the country. Schmidt opened a Rattlesnake in Denver, Colorado, and in Palm Springs, California, as well as other restaurants with his colleague Brian Recor, who is a partner at Lucky’s.

Stephen, 31, said each time his dad would open a restaurant it “became a different home to us.”

“When he was running these restaurants and I barely got to see him, I remember the look in his eye when he’d have us into the restaurants for the first time,” said Stephen. “He would look to me and my sister to see if we liked it, more than a customer, you know. He was just so excited to show us his hard work and we loved working in his restaurants.”

Beyond giving him restaurants to grow up learning in, and techniques to use in the kitchen, Stephen said his dad taught him how to treat staff properly.

“My dad was somebody that only would get angry if it was necessary,” said Stephen. “He would look at every other option possible. He worked being personally close with all of his staff, and that’s something that I always looked up to.”

Stephen considers his staff at Standby to be his “island of misfit toys,” he said. A lot of his crew came from restaurants where they may have not gotten a fair shake.

“I kind of made it so everybody feels very welcome, and I take the people that are very green. And as long as you have passion, I’m very good at being able to maintain that.”

While not having to increase the number of staff members, Schmidt says he’s tripled Standby’s menu, upping it from around seven items to 21.

Located in the Belt, an artistic alleyway in downtown Detroit, Standby is known for its expansive and award-winning cocktail program, which last year earned a semifinalist nod from the James Beard Foundation Awards.

Standby owner and operator Joe Robinson said the team Stephen put together “embodies hospitality.”

“They care about the food, they care about the guests’ experience and they care about each other,” he said.

Taylor, 29, who as a young person made pastries and worked as a host at the Rattlesnake, said one of the things she absorbed working alongside her father was his worth ethic and a passion for hospitality.

“The work ethic was really the main thing that was instilled, the main principle,” she said. “Being in the kitchen, I did really love it, but I think it was a vital component to also have the front-of-house side of my restaurant experience.”

She said it’s the job of the front-of-house (the people working in the dining room, not the kitchen) to interpret the creativity of the kitchen to the guest.

Taylor started working the front desk at the Rattlesnake in her early teens, and was given a front row view to the way regular customers would return year after year to spend family milestones with her restaurant family. As a graduation present, her dad took her to Europe and showed her parts of France he was familiar with from his Chop House days.

After leaving Michigan in 2008 for college in Baltimore, she experienced a different side of the industry while working at a tiny restaurant with a Belgian chef that was a huge departure from the white linens of the Rattlesnake.

“It was the bohemian rhapsody of my restaurant experience,” she said, in contrast to the fine dining background she was used to.

“I came back to Michigan in 2015 and, truthfully, when I came back I didn’t plan on staying for very long. I ended up falling back in love with the city.”

Taylor worked as a bartender at Republic Tavern and other restaurants and transitioned to the Royce Detroit, a wine mecca in the Kales Building that serves as a retail shop and wine bar.

“I would definitely credit a great amount of my interest in going through the Court of Master Sommeliers to my time spent at Royce,” she said. “How often are you able to spend every day around wine?“

It was at Royce where she met Roast sommelier Joseph Allerton, who Taylor says reached out to her about becoming part of the team at the meat-centric, hospitality-forward Roast.

The art of balancing food, family

Both Stephen and Taylor are entering new phases in their lives. Stephen and his girlfriend — Olivia Bonner, who also works at Standby — recently welcomed their first child, Oliver Jet. Sunday will be Stephen’s first Father’s Day, and Jimmy’s first as a grandfather.

Taylor is engaged to artist Steven Johnson, whom she met during her time at the Royce, where Johnson created custom ceramic tableware.

Besides the lessons about a tempered demeanor, strong worth ethic and a personal connection to staff and customers, Jimmy Schmidt taught his kids that you don’t have to run off and be on the Food Network to make it. You can be a successful chef at home and still raise your family.

“The one thing that my dad taught me was truly being able to balance a life,” said Stephen. “Especially with being a dad now, my biggest concern is balancing food and family. He’s always been so passionate. That’s why he’s been my favorite.”

Stephen says he knows his dad still loves what he does because he’ll occasionally see him taking orders at Lucky’s when he’s short-staffed.

“He’ll be behind the register with a smile on his face, because he’s happy to be doing what he loves,” said Stephen. “That’s the world of chefs, man. That’s the real world.”

mbaetens@detroitnews.com