BY BRIAN KATEMAN

It’s been over 25 years since food packaging started displaying its nutritional contents. It’s since become second nature to check the calorie, sugar, salt, and fat content of food or drinks before buying them.

But this isn’t enough for consumers anymore. There’s rising demand for another type of food label as people become increasingly concerned about climate change, and conscious of how they’re contributing to it.

Just Salad recently announced it will display the carbon footprint of every item on its online menu by Climate Week on September 21 this year, making it the first restaurant chain in the U.S. to do so. It also has plans to publish the carbon labels on in-store menu boards.

Each product will list the total estimated greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of the ingredients of each menu item, drawing on databases and research that calculates the carbon emissions associated with hundreds of foods.

The carbon lifecycle of a food includes agriculture, such as fertilizers, manures that emit gases, land conversion that releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and livestock digestion; transportation, packaging and food processing.

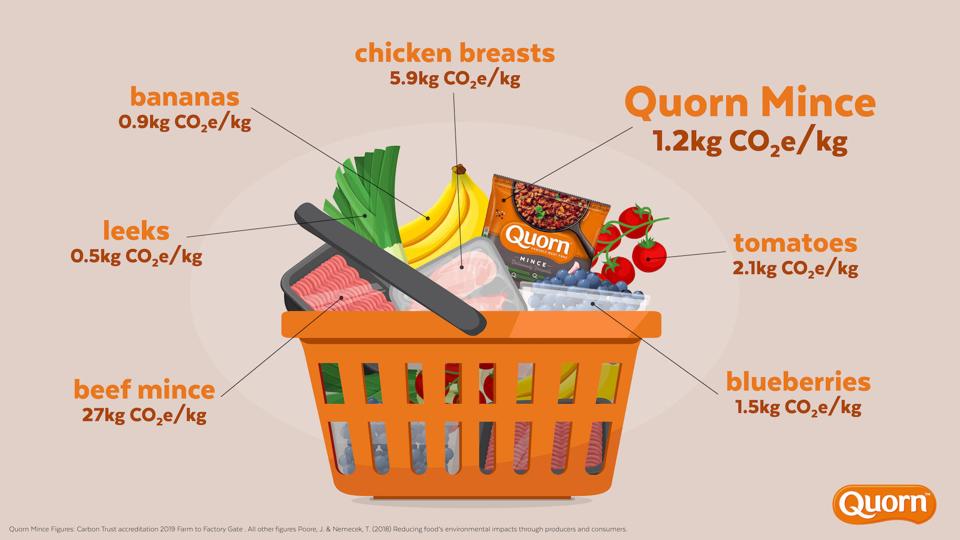

According to the research, vegan foods tend to have a lower carbon footprint than animal products. Enter Quorn, a leading meat substitute company that announced in January it would start carbon labelling on its products available in stores beginning June this year. The U.K. brand has been working with The Carbon Trust since 2012 to measure the carbon emissions of its operations, so it already had the necessary data.

Quorn’s products are all measured per kilogram from farm to shop, so it’s easier for consumers to … [+] QUORN

“People get nutritional data on food packaging to help them manage their health, so we think it’s essential to give people carbon emissions data so they can manage the environmental impact of the food they choose to buy,” says Sam Blunt, commercial operations director at Quorn Foods.

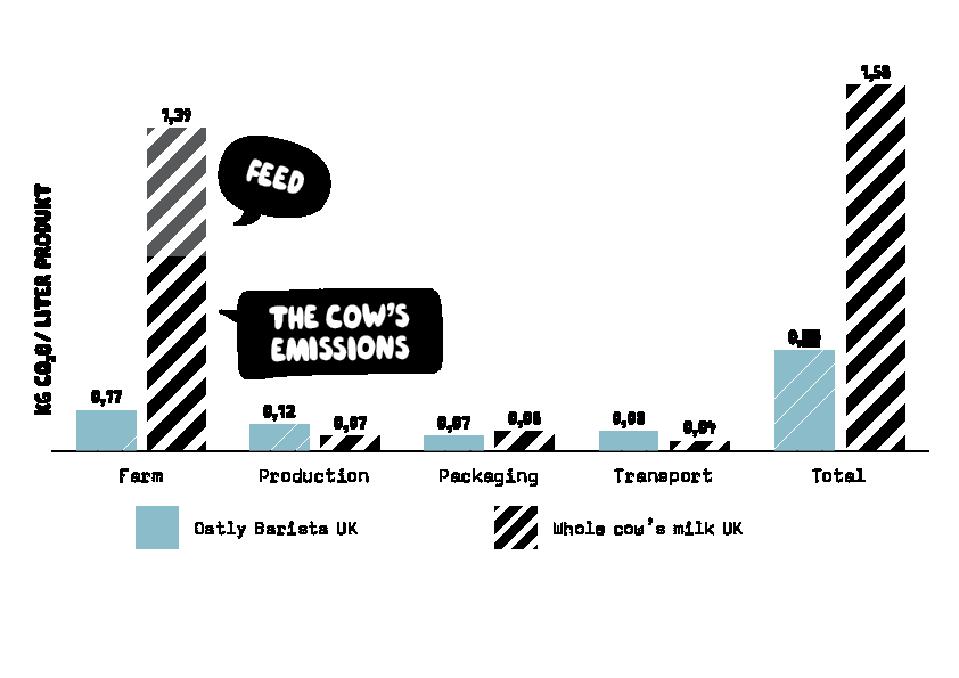

Plant-based milk brand Oatly first analyzed the life cycle of its products in 2013 and decided to put their climate footprint on packaging five years later, after making improvements to its production in Sweden, including switching to using renewable energy. Now, it has carbon labels online and on some product packaging on European products, and is in the early stages of doing this in the U.S.

“We want to raise awareness around the massive effect our food choices have on the climate,” says an Oatly spokesperson. “Many people don’t know the impact of what they eat because that information isn’t readily available. We think consumers have a right to information about the climate impact of what they consume, just as they have the right to information about nutritional values.”

Oatly worked with Carbon Cloud to calculate the climate impact of beverages, including its own.

OATLYThere’s hope that having carbon labels on food will help encourage change on an individual level, and that it will help educate consumers to eat a more environmentally friendly diet. One study found that the labels showing environmental information improved the carbon footprint of a person’s diet by around 5%, compared to standard food labels.

“As people become more and more aware of the environmental impact of what they buy, we absolutely expect carbon labelling to become common-place and for it to influence purchase decisions,” says Blunt.

Currently, food production contributes to 26% of global carbon emissions, and there’s no doubt that emissions on this scale are fundamentally changing natural ecosystems, and reducing biodiversity and ecological resilience.

“Food is the strongest lever we have as individuals for fighting climate change,” says Sandra Noonan, Just Salad’s chief sustainability officer.

If, as a society, we start paying attention to our dietary carbon footprints, much as we pay attention to our daily caloric intake, we could alter the course of planetary history.”

But the impetus to do this already exists and is growing – and the hope is that carbon labelling will help consumers to carry out their desire to lower their carbon footprint. Research indicates that over half of consumers are willing to change their eating habits to help reduce negative environmental impact, while a survey of 10,000 consumers in Europe showed that two thirds supported carbon labelling of products.

The brands starting the nascent carbon labelling movement are hopeful the introduction of carbon labels will also help drive improvement across the food industry.

“We hope there will be healthy competition to ‘race to the bottom,’ in terms of emissions,” says an Oatly spokesperson.

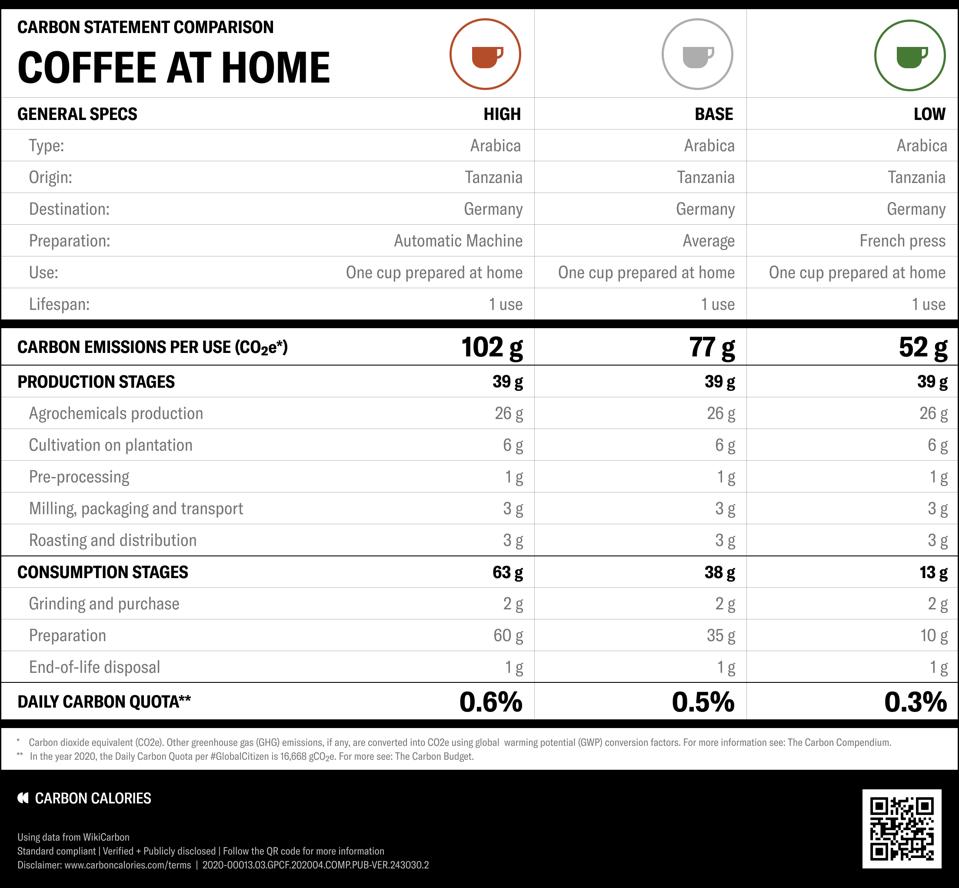

Behind the food chains and brands introducing carbon labels to their food, there is the important work of analyzing individual food items’ carbon footprint. Carbon Calories is one of the companies producing carbon footprint reports aimed at consumers, showing grams of carbon dioxide emissions per day.

This allows consumers to compare products, including food and other products, such as clothes and vehicles, using the same metric. Its database also shows these products’ carbon footprint against a daily carbon quota, so consumers can weigh up their consumption decisions against a daily goal.

Alexander Frantzen, founder and chief executive of Carbon Calories, believes that consumers, when they become aware that companies can provide carbon footprint information on products, will influence companies not just across food, but all industries.

“Once a few brands begin to put carbon footprint labels on their products, we believe that consumers will use that information to inform their decisions; and will begin to demand it from other companies,” he says.

How we prepare our coffee can have a big impact on the carbon footprint, in addition to efforts made … [+] CARBON CALORIES

Frantzen believes that when customers can make such informed decisions by a handful of companies, it will compel other companies to do the same.

“If [these companies] can determine and deliver product carbon footprint assessments for their products, then other companies can and should likewise step up to the plate,” he says. “This is not about shaming. This is about assessing where we currently stand and then transforming business activities to reduce emissions.”

According to research, the introduction of nutritional labelling reducedconsumers’ intake of calories by almost 7% and total fat by over 10%.

Robert Shirkey, Executive Director of Our Horizon, a national not-for-profit organization that works with governments to require climate change disclosures on gas pumps, views these developments as a positive step, but argues we need to work to make the messaging more explicit, since carbon emission units aren’t meaningful to most consumers. “It’s like if we had labels on cigarette packages that read, ‘Each cigarette contains 10 mg of tar.’ What do these values even mean? How does it affect me? These sorts of designs connect ‘a’ dot but not ‘the’ dots. Instead, we have tobacco labels that say, ‘Smoking causes cancer.’”

Noonan agrees that context and education is critical, and sees opportunity to bring greater meaning to the emissions data. “We’re developing materials that will explain how to read a carbon label, make sense of the actual number, and incorporate that information into one’s daily food choices. We have lots of ideas on sharing this information visually and making it engaging. For example, in the nutrition facts section of our menu, we plan to show how a salad’s carbon footprint compares to a ‘reference food.’”

If carbon labelling can become as ubiquitous as nutritional labels, then it might not be too long before it has a meaningful impact on individual dietary change, and by extension, the food industry as a whole.

“Consider all of the things we track in our lives on a daily basis: our bank account to see where we are spending our money, and tools like My Fitness Pal to see how many calories we’re ingesting according to the recommended 2,000 calorie amount per day,” says Noonan. “Showing the carbon footprint of a food item should be no different, and should serve to inform people to make educated decisions for personal and planetary health.”