Researchers have discovered how a mysterious part of the inner brain distinguishes salty from sweet, bitter from sour. It all happens in the same region that regulates emotion—which explains a lot.

March 20th, 2019

by Jessica Fu

Scientists have recently gotten one step closer to solving an intractable mystery: what food tastes like to the brain.

Like the ocean floor and the dark web, the human brain is still largely unmapped. Recent research has tried to fill out that map by outlining how the brain, and its intricate system of 100 billion neurons, makes sense of sensory information. But while scientists have figured out how sight, hearing, and touch translate into neural signals, they’ve long failed to map the “gustatory cortex”—or, the patterns that result as a response to tastes in the mouth.

One reason it’s so difficult to show how taste registers in the brain, says Cornell University cognitive scientist Adam Anderson, is because our feelings keep getting in the way.

Whenever we eat, our brains light up with activity. But it’s not easy to separate brain activity related to taste from the more subjective experience of enjoying that taste. Say you eat a bite of cake, for instance. How can scientists tell which neurons are firing specifically in response to the cake’s sweet frosting, and which are firing for emotional reasons related to pleasure, satiation, and the memories of celebrations past? This newfound understanding could help us reconsider how we think about nutrition.

To get a clearer picture, Anderson’s research team at Cornell wanted to try to isolate the physiology of taste from the the emotional side of eating. To do so, the team conducted taste tests—a lot of them. Their findings were publishedthis month in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

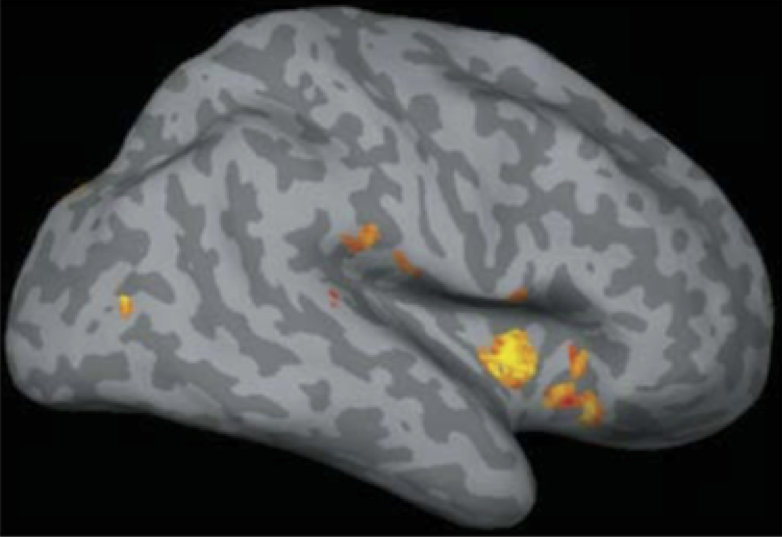

First, the team created four chemical mixtures, each representing a certain taste: citric acid for sourness; table salt for saltiness; quinine, the flavor agent used in tonic water, for bitterness; and sucrose for sweetness. Then, it poured these solutions in random order onto test subjects’ tongues. Participants rinsed with water between each tasting to cleanse their palates. They were also asked after each sample to rate how pleasurable the taste was. While this was all going down, participants’ brains were scanned with an fMRI machine, which collected data about brain activity. By the end of the experiment—which consisted of 100 taste tests on each of the 20 participants—Anderson’s team had amassed a significant data set showing how the insular cortex, the “taste center” of the brain, behaves depending on taste.

Because Anderson had documented his participants’ sense of pleasure during each test, he could group brain scans not only by taste but by emotion. As patterns emerged, it allowed his team to screen out the brain activity related to feelings, and see how bitterness, sourness, saltiness, and sweetness registered. The result? The clearest understanding yet of how the brain maps taste sensations.

“If we zoom in on a particular region in the insular cortex, we’re finding that the specific patterns of activity in there tell us what’s on the tongue,” Anderson explains. “That has been really revealing.” Read morehttps://newfoodeconomy.org/taste-brain-insular-cortex-sensory-map/?mc_cid=ed8a5cc0ce&mc_eid=a7b9c32c76